On our sixth wedding anniversary, my husband gave us a firebox. A black, indestructible plastic case similar to a briefcase. The traditional gift for a sixth wedding anniversary is iron to represent the "ironclad” love between two people. The firebox has a hard exterior black shell, much like an ancient turtle. “Turtle” is one pet name for my husband — he is steady and takes life at his own pace, the perfect opposite of my anxious tendencies. The box itself measures seventeen inches long and twelve inches tall, with a depth of approximately six inches. It’s heavy, around thirty pounds, adorned with a round metal lock that uses a circular key to access the interior, which is oddly much smaller than I expected. Its main objective is to protect paper documents. I hadn’t requested it specifically as an anniversary gift. However, my husband and I are pragmatic and often give each other gifts to reflect our overall practicality, preferring to spend our anniversary day at an art museum followed by a coffee and pastry shared between us. The firebox was practical and would keep our family safe (or at least our dog's medical records and various other financial documents intact).

His purchase of this gift was not out of nowhere. Months before our anniversary, I had been Googling ways of keeping material objects safe, mainly journals, delicate and flammable documentations of time. I knew some people were buried with their journals or lit a fire once a year and burned everything they wrote in these private books. Some stowed them away in steamer trunks, which acted as coffee tables. I liked that idea, both practical and aesthetic. However, none of these options solved my unique problem of wanting to keep something safe and live with its daily visual presence. I then began to wonder what other objects I would save in an emergency and how this box would keep them safe. In a world where everything can be digitized, what is the use of a fireproof, disaster-proof box? I understood the implication of not keeping these objects safe and impenetrable from outside forces. The material that could be lost in these objects, many of which had been passed down or created by my hand. But I also wondered what would happen when they were no longer visible. Would they cease to exist? Would a new form of them appear in a new timeline, a Schrödinger’s cat of mementos inside its box?

I knew rationally that the objects would continue to exist even when unseen. But on an emotional level, I feared that valued items or people would disappear. Infants develop object permanence at only a few months old—they understand that just because they can’t see a beloved toy or parent doesn’t mean the individual no longer exists—they are just not visible or able to be touched. I’m sure I developed this fundamental understanding as an infant. Still, along the way and into adulthood, I’ve lost a part of that understanding, or it’s slowly been eroded, leaving me desperate—clinging to thoughts in an attempt to get everything down on paper, to let it exist and breathe life outside my mind. Holding onto minuscule pieces of nature as artifacts. A ticket stub from a concert is a more vital reminder than the memory. We place valuable items in vaults, safes, and banks. Often due to their monetary value, but what about emotional value, even the person they are connected to?

I grew up in a home where I was raised to always prepare for the worst, knowing you can care for your family and keep them safe. As an adult, I’ve implemented emergency protocols for tornados, hurricanes, loss of power or water. Grab the dog, pillows, and a gallon of water and go to the emergency closet. A linen closet in the center of the house, protected by a hallway. Growing up, I learned how to work a generator and stay up all night to listen for what my dad called the train roars of a tornado. If he wasn’t home because of his job at a chemical plant requiring him to go in during natural disasters, I would be in charge of keeping myself, my mom, and the dog safe.

I have grown up with the knowledge that I nearly lost my dad when I was only five days old. On July 5th, 1990, my dad was called into work at ARCO Chemical Company in Channelview, Texas, leaving my mom home alone with a newborn. The men on Dad’s team insisted he work inside instead of outside that day just in case his wife called. During routine maintenance, there was an explosion and resulting fire that destroyed the equivalent of an entire city block, burning for four hours, killing seventeen and injuring five. My dad’s friends who wanted him to work inside near a phone that day were killed while his life was protected within walls. When I couldn’t sleep as a child and would run to him and Mom for comfort, he would tell me how difficult closing his eyes at night could be, too—behind his closed eyes, he would see his friends burning in front of him. He would then dip his large, tanned, rough-worked hand into a gallon of Holy Water, which he kept under the bathroom sink, and trace the sign of the cross on both our foreheads.

This was a truly horrific story to tell any child, especially an already anxious and sensitive one. Still, my dad never tried hiding the realities of what could go wrong in life, instead choosing to be honest to best prepare me. My mom, however, didn’t appreciate him putting these images into my head but saw how cautious and prepared I became as I got older, how little to no trouble I got into as I entered my teen years, and how few extreme chances I took.

Growing up as a child raised to always prepare for the worst, I played and practiced disasters with my toys. Playing with my plastic bubblegum pink heart-shaped Polly Pocket that fit into the palms of my hands—it opened and closed like a seashell with miniature furnishings similar to a shrunken down doll house. Polly had a stiff yellow plastic ponytail that I’d swish around. (However, her ponytail stayed perfectly in place) as I had her chase her plastic golden retriever puppy around the beige carpet of our living room floor. I also had a plastic red barn with a faux wood embossed plastic fence that held horse figurines, plastic hay bales, perfectly ripe red plastic apples, and a silver-painted water pail. I’d set everything and everyone up perfectly like a showroom. Horses were safe within the barn, and Polly and her puppy were snug in bed when disaster would strike. I would shake the now closed pink heart and wooden barn, exclaiming with alarm that a tornado was coming through, that it would be over soon, and everything would be ok. Looking back, it's unclear who that statement was meant to comfort more. A few seconds later, after the wind had settled and it was safe to go outside, the horses would emerge, Polly would walk out to assess the damage, and I would place everything back as it was. I remember feeling proud, knowing I knew how to respond in an emergency, get the animals securely in the barn, and ensure they had food and water. I would repeat this over and over like a drill.

In my childhood bedroom, I hid rocks, flowers, little treasures, figurines, and a floral-patterned journal with a tiny silver lock and key under my bed along the inner edge between the bedframe and mattress. I could sit comfortably underneath as it sat atop a tall boxspring. The bed had a ruffled lavender bedskirt that touched the floor, creating a cave where I could gaze at the museum I made with the things I found valuable and beautiful, worthy of only my eyes. I was curating an exhibit before I even knew what that was. My mother and I agreed that this was sacred and would not be touched during her cleaning in exchange for my not entering the kitchen after she mopped the floors with astringent vinegar. Our individual sanctuaries were respected as holy ground. Mom also agreed that I could keep my bedroom door closed when my three rowdy boy cousins were visiting, fearful that their rambunctious tendencies and perpetually sticky fingers might knock my treasures out of their poised positions. When my mom couldn’t find me around the house, she knew I was likely under my bed, arranging and rearranging my treasures.

When Dad wasn’t working his regular job at the chemical plant, he was doing handyman work, which he grew up doing with his father, too small to be on rooftops in the grueling heat of South Texas. I often spent weekends and school breaks assisting him at other people's homes. His job kept him working fourteen-hour shifts, switching between night and day shifts. While he needed the extra hands on the weekends and school holidays, painting homes and fixing toilets and leaks, he also saw it as an opportunity to teach me basic handy skills, and it was his way of spending time with me. If he couldn’t find something for me to do that day, he would hand me a piece of scrap wood, a heavy steel hammer too big for my child-sized hands, and a handful of iron nails and tell me to practice hitting the top of the nail head straight down with the metal flat of the hammer with a sure —whack—. If the nail shaft went into the wood crooked or splintered the wood, I was instructed to pry it out of the wood, grab a new nail, and try again. Whack—WHAck—WHACK!

Dad always found an interest in the things I was devoted to—finding ways to connect with me through my cherished objects. I was like a shadow box to him. He could see what I valued by beholding each object I held close. We would often pick up tiny rocks and seashells on summer family trips. Once, he sneakily removed an ordinary gray rock from Alcatraz Island, revealing it from the inner pocket of his windbreaker once we were on the ferry back to shore, giving its ordinariness a magical quality. He loved buying me trinkets like a bottle of colored sand poured to form a landscape of the ocean and sunset on a beach in Mexico or pouches of minerals from a trip to the mountains of North Carolina, polished and smooth.

Dad never left home without kissing my mom and me goodbye, often taking a few extra minutes to pack his truck for a night shift, delaying, knowing we would be home from school at any moment. Placing two or three quick kisses on each of our cheeks or foreheads, bristly and rough from his thick black mustache, smelling strongly of his cologne that would often wake me up at three in the morning as he walked down the hallway past my bedroom for a day shift. Each time he drove out of the driveway for his hour-long commute on I-45, I imagined what disaster could occur, drunk driver, severe rain causing him to swerve, anything you can think of I imagined and likely imagined it to be ten times worse. While we all fear a disaster taking a loved one, I felt even as a child as though the child version of myself was somewhere existing in another timeline where I did lose my father in July of 1990.

I always believed that if a parent was out of sight or not under the same roof, something would happen to them. I placed all of this fear on my mom. Existing within each other’s orbit at all times, mothering each other equally. I treated her as a godlike mother who I needed constantly, and I, in turn, required her constant attention to assuage my own fears that did not ease as I got older.

In 2021, she was diagnosed with stage four metastatic breast cancer, and a part of my understanding of the world fell apart that day, unwillingly realizing I couldn’t protect her the way I always believed I could. Something unseen within her was taking over, and I never saw any outward indications. She didn't need to tell me. I already knew. Waking up that morning, I knew something wasn’t right as I saw my parents walking up to my front door through the kitchen windows where I was anticipating their arrival. I waited an extra few seconds before opening the front door to preserve the moment life was still one without cancer. I remember Dad bracing against my kitchen table, my husband close by, and my mom with me standing near the couch when she told us. I fell into her arms, needing her to support me in a way only a mother could. As I glanced over in fits of sobs, I saw my husband trying to hold himself together and was confronted with a look of defeat on my dad's face. At that moment, we simultaneously realized his failure—he hadn't prepared me for this disaster or its sudden entrance into our lives. He couldn't protect me from everything. My parents are not immortal—I cannot keep them in that state.

My dad and I both continue to carry the weight of fear, the near loss of each other, and now, the inevitability of losing a wife and mother. The potential for disaster has shaped how he raised me and how I move through the world of objectivity and the things and people I love. While we acknowledged the gift of a long life with each other, we also continue to hold space for the story that didn’t contain that future. It caused me to grow up holding onto parts of people and the things they have touched in a way that can’t be described, like anticipatory grief. Experiencing the loss before it ever happens, a sort of everlasting mourning.

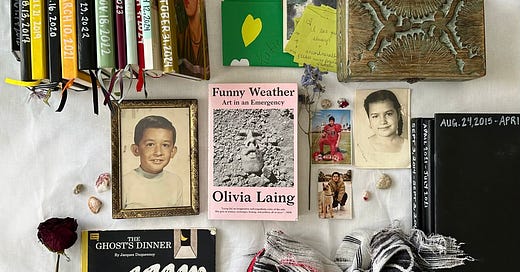

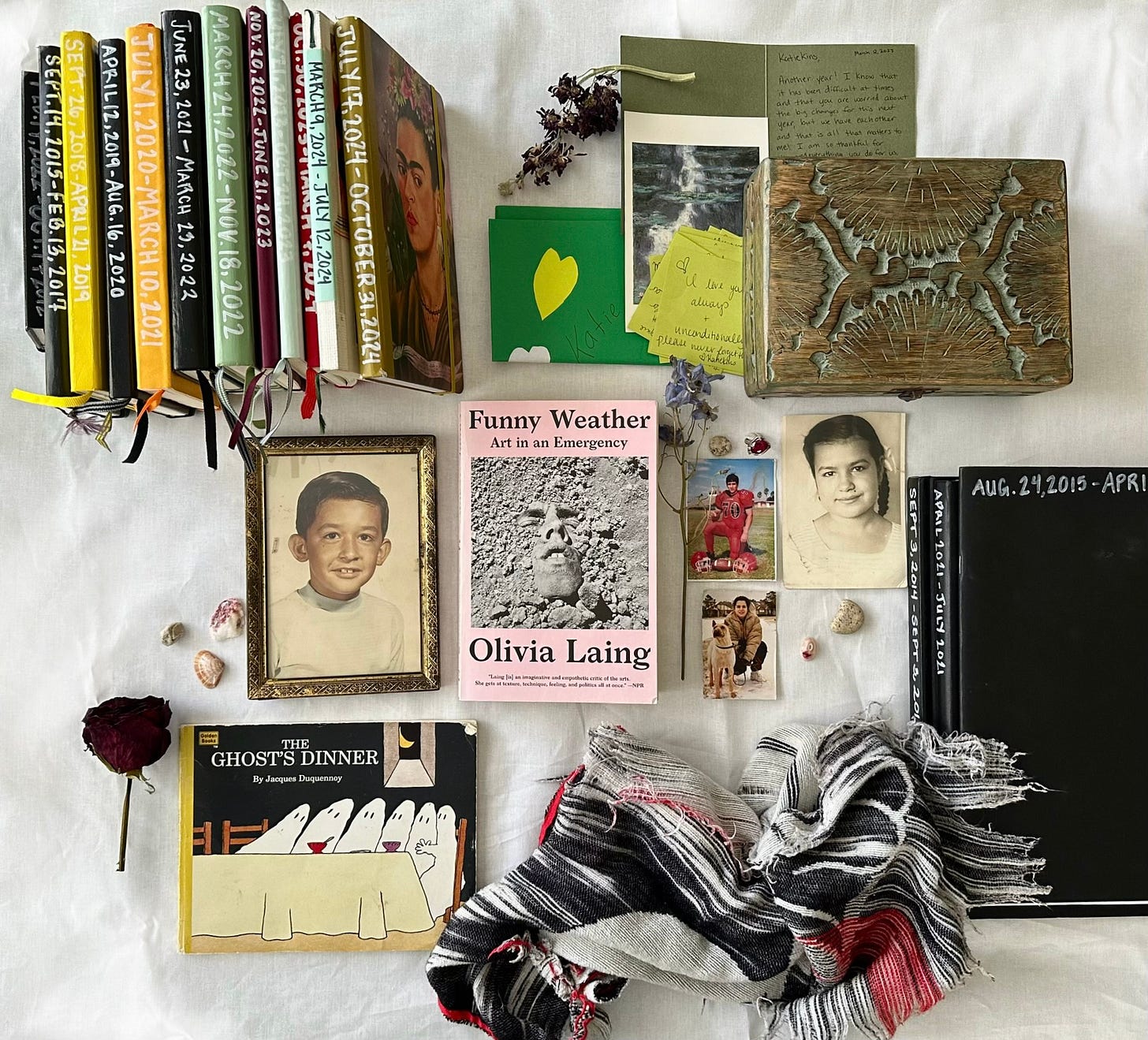

Throughout my adult home, objects retain memories. An assemblage of the past and present are displayed and arranged in nooks and crannies, shelves and altars, imbuing them with sanctity, a scene for devotional reverence. Detritus from walks are collected and ingrained with a history invented in the present moment. The refrigerator is an homage to a ten-year relationship, magnets of favorite artworks, long expired coupons, and our nephew's drawings. Journals are lined up on a shelf in my office like a timeline in a history textbook, only the chunks of months scrawled on the side in white paint marker, like orderly soldiers of time. Many of these coveted objects are gifts from my father, colorful shells and rocks he thought looked interesting, brought back from trips he and my mom went on. He will sit to tell me a story about each, the place they came from, setting the scene of the object's history.

Nearly two years later, the firebox sits empty. I can’t seem to put any items into it. I need to live with these objects—they wouldn’t all fit inside the box anyway.

An inexpensive ruby ring from my grandpa to my grandma set askew and encircled in a deco-style silver band with two shards of diamonds. A photograph of my mom, three months pregnant with me, during a rare Texas snowstorm with our dog Buster. An oxidized gold-framed school photo of my dad, in the third grade—my nearly identical twin. Tucked into the frame are other school and family photographs from his childhood. A black and white school photo of Grandma around the age of eight with her hair in a braid with a bow. My cousin “Little Willie,” in his red number 70 football jersey taken during his senior year of high school, a few months before he passed away—we were only five months apart in age. A carved wooden box with birthday and anniversary cards and multiple sticky notes my husband and I would leave each other when we first started dating. It’s becoming tough to clasp shut. Journals and sketchbooks from 2012-present, approximately fifteen volumes in various shapes, sizes, and colors. Falling apart baby blanket held together in some places by flimsy threads. I still hold it delicately in my hands and gently rub it between my fingers when I’m feeling anxious—I named it Woobie. One heavily dog-eared and annotated copy of Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency by Olivia Laing and The Ghost’s Dinner by Jacques Doquennoy, a children’s book I’ve had since Elementary School. Rocks, figurines, and dried flowers, too many to count.

In facing these objects’ daily existence, I see their unique importance in my life. I am seeking ways to understand their impermanence and their material fallibility, like that of mortality. They are talismans offering a false sense of security. I’m not in Noah's position to decide who can go safely into the ark and who must stay and face disaster. Every severe storm, my husband and I drag the firebox across the floor out of the emergency closet and replace it with ourselves and the dog with a pillow and a gallon of water.

Damn Katie, this made me tear up. I love the full-circle momentum of this piece, and the way your childhood and love for your parents really shine through. I also relate so so much to the anticipatory grief and constant fear of disaster. Your desire to archive and document made me think of one of my faves: Archive Fever by Jacque Derrida. I hope you never stop writing and sharing!!

Thank you Katie for sharing this piece. I truly enjoyed every moment of it. It is so moving and intimate, just beautiful. And just two days ago I was thinking about what objects I have are dearest to me and if I should maybe have a box to store them in order to easily take them with me in case of emergency, so this piece really came at a perfect time. Thank you <3